ART WORLD NOTES

MAGAZINE Vol 35

2016 – Semester 01

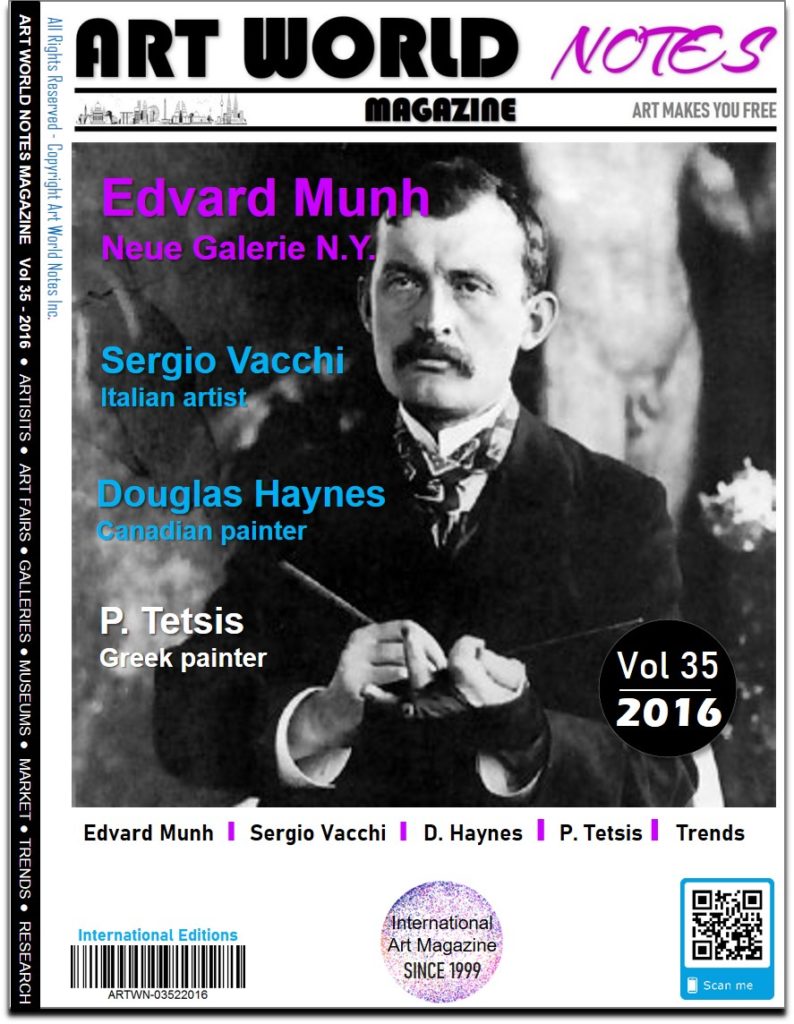

Edvard Munh Neue Galerie N.Y.

Cover: For more than a century, the reputation of Edvard Munch has circled the canon of modern art like a big plane seeking a runway. He is famous, sure, for the flayed, undulating figure of existential panic in “The Scream” (1893) and for a few other images, touching on love and death, from the first, rock-star-like decade of his career. But the subsequent, prolific glories of the Norwegian painter, who lived until 1944, are little recognized.

Munch is all but placeless in standard art history, not exactly a marginal case but definitely a singular one. “Munch and Expressionism,” an exciting new show at the Neue Galerie, settles his one textbook claim to historical consequence: he is the father of the most important modern movement in German and, to some extent, Austrian art. “Without Edvard Munch, German Expressionism would not have existed,” the art historian Reinhold Heller states in the show’s excellent catalogue. In the first years of the twentieth century, young German artists, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff—and, less directly, the Austrians Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka—were galvanized by Munch’s painterly eloquence and emotional candor, and by his innovative use of woodcuts and other printmaking mediums. They and their supporters lionized him, though he largely shrugged off their blandishments. He was an artist, and a man, apart.

Powerful Expressionist works in the show, such as Kirchner’s sensational touchstone, “Street, Dresden” (1908), perform like an honor guard for forty-seven Munchs, including not the original “The Scream”—which was done in oil, pastel, casein, and crayon—but the artist’s calmer, even elegant, 1895 copy of it, in pastels. (This picture became briefly the costliest art work ever sold at auction, four years ago, when it fetched nearly a hundred and twenty million dollars at Sotheby’s, in New York.) For reasons that beg to be explained, the works by other artists in the show do not measure up, with the one late exception of “Self-Portrait with Horn” (1938), by Max Beckmann, a true peer, whose tragicomic ironies transcend Expressionism. The originals of Munch’s early masterpieces—“The Sick Child,” “Death in the Sickroom,” “Evening on Karl Johan Street,” “Puberty,” “The Voice,” and at least half a dozen others—are absent but for the transfixing landscape “White Night” (1900-01), in which dark, contorted trees loom against an off-white expanse of water and a star-speckled blue sky. Most of the Munch paintings in the show come from the Munch Museum, in Oslo, but his best works reside in that city’s National Museum, in a huge room that has changed some visitors’ lives.

A concentration on secondary work has its virtues, however. Partly, it levels the terrain somewhat for comparisons with Munch’s epigones—his valleys meet their peaks. More important, it encourages absorption in his talent’s essential qualities, which persisted after a series of nervous breakdowns led him, in 1909, both to reform a dissipated life style and to mute the psychodrama of his halcyon art. In “The Artist and His Model” (1919-21), thickly brushed in oils, Munch stands stonily behind a taciturn girl in an unusually detailed, seething interior of a house in Ekely, near Oslo, where the artist, who never married, lived alone for his last thirty-two years. The way that the paint moves on the canvas is as compelling as what it describes.Munch had ceased to take narrative ideas as a starting point. Instead, he teased hints of meaning from gladiatorial wrestles with paint, and occasionally the result became iconic. In a stunning self-portrait, “The Night Wanderer” (1923-24), he cranes forward and gazes out tensely, as if suspecting an intruder. Always, there’s the uncanny refinement of his touch. Nearly every stroke or dab, even when piled or flurried, has an integral tension and a just-right quotient of energy. But late Munch is a barrel of hits and misses, and one painting in the show, “Standing Nude Against Blue Background” (1925-30), scrapes the bottom. He was fine with preserving his botches, while according them scant respect. He took to leaving his paintings outdoors through the brutal Norwegian winters—to “kill or cure” them, he said.

Munch was born in 1863, into poverty, the son of a lowly and fanatically religious military doctor. His mother died when he was five, and his beloved older sister, Sophie, when he was thirteen. Another sister became psychotic. A kind aunt helped with his upbringing and encouraged his studies in art. In Kristiania, as Oslo was then known, a radical bohemian scene besotted with Nietzsche cultivated Munch’s precocious genius, but its advocacy of free love ill-served his sanity. The traumas of a harrowing affair with a cousin’s wife, followed by other relationships that were scarcely happier, played out in such stunning paintings and prints as the beautiful and dire series entitled “Madonna”: a woman in orgasm as seen by her lover, to whom she is supremely indifferent. Two printings of a lithograph of the image realize astonishingly different nuances of the drama with a simple change of color density.

The young Munch profited from a government program that paid artists travel stipends. In France and Germany, his initial naturalist manner gave way to variants of Impressionism, then leaped to something unprecedented, in representations of life lived, with hard truths and quaking sensitivity, on the brink of derangement. The state censors shut down Munch’s first major show, in Berlin, in 1892, but it made his name, and was followed by many more shows in Germany. (A number of his major works were owned by museums and collectors there, until the Nazis confiscated them and sold them off in Occupied Norway.) The key to Munch’s originality is storytelling with a potent pictorial rhetoric of rhythmic line and smoldering color. Each work feels like a one-off personal emergency, even when it is repeated in other paintings or prints. The Expressionists adopted the look of his style, which serviced their drive to counter French formalism by stressing the psychic toll and the compensatory exhilarations of the modernizing world. But Munch’s sincerity was bound to elude them.

“If only one could be the body through which today’s thoughts and feelings flow,” Munch wrote in 1892, when he was abetted in his ambition by a circle of artists and writers, including his close friend August Strindberg, who met regularly at a Berlin bar called the Black Piglet. His success in that realm is part of what makes him slippery for art historians, who might otherwise acknowledge a level of achievement that, for me, ranks with that of van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, and Seurat. Munch is too humanly interesting! He sacrifices the aesthetic discipline, the detached immersion in the problems of painting characteristic of the leading Post-Impressionists. (He is closer to the symbolist broodings of Édouard Vuillard but drastically less tactful.)

The Expressionists often convey—or even, like Schiele, advertise—their personal familiarity with the bold, the louche, and the lowdown, perhaps as a sign of enviable cool. You can’t presume to match their experience. Munch suggests—concerning his bouts with lust, dread, and despair—that you more or less already do. This makes him a discomfiting study for a next-slide-please survey course. Having no notable self-regard, he gave himself wholly over to art. (I’m struck by a thought that, for the sheer availability of an inner life, Munch has a latter-day Norwegian avatar in the writer Karl Ove Knausgaard.) The Expressionist whom Munch liked most was Emil Nolde, another thornily independent spirit, who is represented in the show by a large lithograph, “Young Danish Woman” (1913), and three hand-colored repetitions of it: works of fantastic intensity, with distorted features and dissonant colors, that dare unusual ugliness to take unusual beauty by surprise. They are true to Munch’s insistence on having every drawn or painted mark register a motive or a feeling. But even Nolde—who, incidentally, fell prey to Nazi sympathies, as Munch did not—tends toward generality in what he expresses. Munch specifies. His example to other artists is simple, really: be a highly gifted but, especially, a particular person, and go for broke.