ART WORLD NOTES

MAGAZINE Vol 12

2004 – Semester 02

Lucian Freud Figurative art

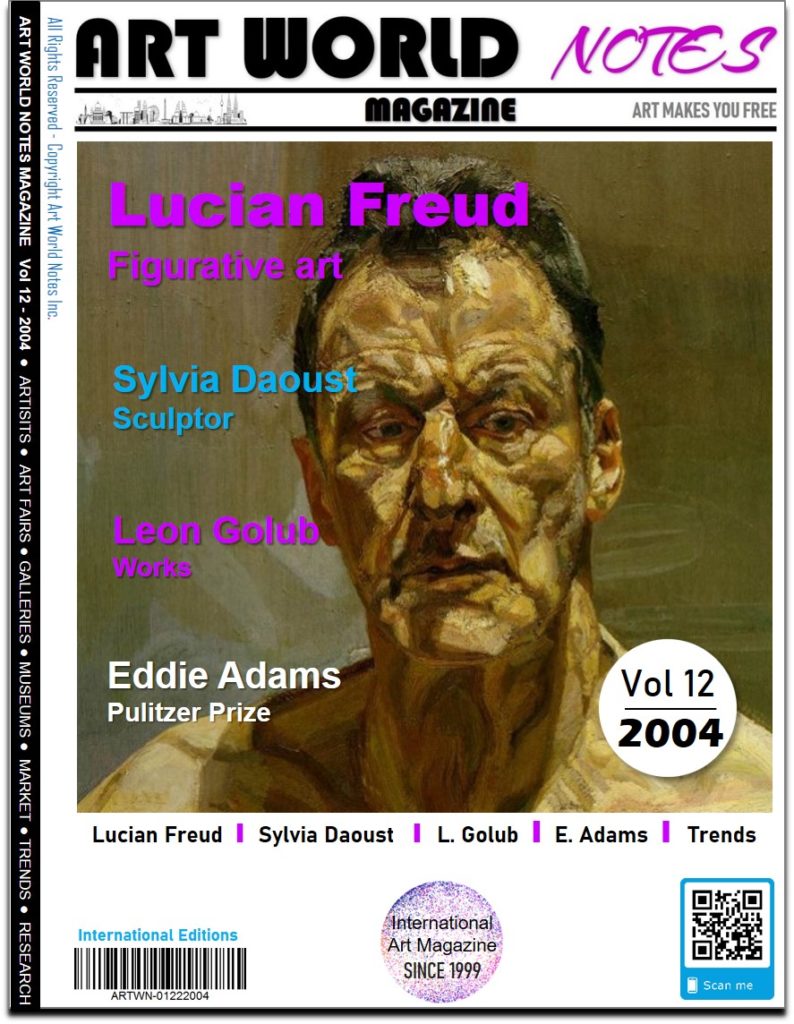

Cover: Lucian Freud. At 81, Freud is so much younger than any of the Britart dreck installed on the other side of the Thames: younger than Damien Hirst’s slowly rotting shark in its tank of murky formalin; weirder than David Falconer’s Vermin Death Star, which is composed of thousands of cast-metal rats; and about a hundred times sexier than Tracey Emin’s stale icon of sluttish housekeeping, her much-reproduced bed. His work is supremely tough, ruthless even.

But it has none of the facile emotional posturing that appeals to the kind of institutional adman’s taste, the bratty cynicism and quick-fix sensationalism that pervades the Saatchi collection. In fact, Saatchi once owned a number of Freuds, some of exceptional quality, but then he sold them off; perhaps, in the end, they were too grown-up for him. Or perhaps, when you come down to it, the man is just another dealer, and not a very distinguished one at that, with no actual, earned right to be thought of as a leader of late-modernist taste. The whole exercise in mythmaking was just a noisy sprint up a blind alley. New Blood is an utter fiasco.

But there Freud is, where he ought to be: a genuine national treasure, briefly ensconced in one of England’s (and the world’s) supreme collections. There are logistical problems – the little gallery is hardly more than a lobby between two much larger ones, so that the Wallace, unused to crowd control, has had to limit the number of visitors to 50 in the room at a time; how that will work out, we have yet to see.

Things weren’t always like that. Plenty of people, and not old ones either, can remember a time when people certainly didn’t get in line to see such work, when Freud, instead of being placed alongside Edward Hopper in the pantheon of modern painting, was seen (if glimpsed at all) as a mere afterthought to the world triumph of American abstract art. Many art-folk in the 1960s and 70s would have thought him “less interesting” than Andy Warhol (no doubt some still do, but they are fools). What one sees in this show, and takes away from it, is a triumphant vindication of painting’s rights of claim. The way Freud perceives a form and builds it up from oily mud on a piece of cloth; the way he constructs analysed equivalents to reality – all that, at best, is inspiring. It represents an order of experi ence totally different from the relatively weightless coming-into-sight of a photographic image or a silkscreen.

This is not a claim for moral superiority. But it does seem, at least to me, to indicate where traditional painting of the kind Freud does shows its perceptual superiority over photo-derived art. Every inch of the surface has to be won, must be argued through, bears the traces of curiosity and inquisition – above all, takes nothing for granted and demands active engagement from the viewer as its right. Nothing of this kind happens with Warhol, or Gilbert and George, or any of the other image-scavengers and recyclers who infest the wretchedly stylish woods of an already decayed, pulped-out postmodernism.

And it is a curious part of the “Freud effect”, if one can so call it, that one feels no bump, no awkward transition, in passing from one gallery of the Wallace Collection, with its Rubens oil-sketches, to the room the Freuds hang in. Both are manifestly part of the same tradition, the same noble continuity of pictorial eloquence. You are not looking at an “original” and an “imitator”, at “source” and “quotation”. Nobody knows more clearly than Freud himself that he is not a reborn Rubens (or Hals, or Watteau, or Géricault, or Manet, or any of the other objects of his homage). That kind of rhetoric is for boastful dolts such as Julian Schnabel or Jeff Koons. To call Lucian Freud “humble” in the face of his great mentors is both to understate things and to miss the peculiar intensity of his fascinated arrogance.

The Wallace has set forth a big tranche of Freud’s work. He has always been notable for his slowness. He takes for ever to finish a portrait; nothing hurries those furrowed crusts of paint, those deadly poisonous white kilos of lead oxide. All the less expected, then, to see how much work he has put behind him over the past couple of years. Nearly all the 22 paintings and etchings at the Wallace were finished between 2002 and this year.

In fact, the enormous image of his friend, assistant, photographer and frequent model David Dawson, splayed buck-naked on a day-bed in the studio – his imposing scrotum looking larger than the pillow behind his head – was only finished at the last moment, just before the van came to take it away to Manchester Square. (An exhibition of Dawson’s own photographs, including a remarkable image of David Hockney posing blockish and silver-thatched alongside his portrait by Freud, has just opened at the National Portrait Gallery.) One is put in mind of another great English painter, Turner, adding mysterious spots and smears to his landscapes on varnishing-day at the Royal Academy.

This portrait of David and Eli, 2003-4 (Eli being a nervous, alert whippet, whose quick sit-up glances are so reminiscent of Freud’s own facial expressions, sidelong and knowing; here, though, it drapes languidly down the bed, in a posture of almost sybaritic trust) is the show’s masterpiece. It possesses an amazing structural toughness and Dawson’s body, though in the act of reclining, seems at the same moment to tower over you: a doubling whose strangeness seems only to grow the more you look.

But although one may recognise in this painting an amplitude and confident grandeur which, you might think, had vanished from English portraiture with the deaths of Sargent and Sickert, it isn’t by any means the only memorable human image in this show. There are the strong, long-boned female nudes. There is the almost overwhelming presence of Andrew Parker-Bowles, unbuttoned but extremely fierce, in the uniform of a brigadier, red stripes blazing, blood beating its tattoo under the skin, the head with its bony and meaty facets looking weightier than a cannonball – a long-delayed riposte, one might suppose, to Manet’s Fifer.

And there are the animals. Perhaps no one has brought more feeling to the scrutiny of dogs since Landseer, though Freud would doubtless prefer a comparison to Stubbs. The task of depicting dogs – particularly beloved ones – attracts false feelings like fleas, but Freud’s great etched portrait of Eli is all objective animal, no phoney “humanism”. Even when he paints the grave of Pluto, Eli’s predecessor (rather confusingly, Pluto, though named after the male god of the underworld, was a whippet bitch), he doesn’t get soppily reminiscent: it is just a little wintry patch of earth and leaves.

A lot has been written about Freud the unsparing analyst of character – too much, perhaps, and often lopsidedly. The fact that he is one of Sigmund’s grandsons does not do a lot to characterise the feel of his work, which, despite early parallels to German Neue Sachlichkeit portraiture in the 20s, is more often lyrical than clinical, though the lyricism sometimes partakes of melancholy. Witness the enchanting little picture of Freud’s grandson, the little boy Albie, with his cheeky lobe of tongue poking out; or even more, the portrait of Frances Costelloe, 2003, a girl given over to absorption like any young woman in Chardin, dreaming with her head on a pillow, as perfect a realisation of inwardness as modern painting has to offer.

The analysis painting can offer is very different to the analysis of a shrink, and the narratives of form in Lucian Freud’s work are, above all, formal. What they often reflect is not so much a psychic transaction between sitter and artist, as the sheer tedium of submitting oneself to the painter’s constant scrutiny, hour after hour, in the studio light. The eyes glaze and look inwards. But not all the time.

There is a lot more humour and sweetness in Freud than he is credited with – it’s just that his unsparing wit and pitiless judgment, which allow the sentimental no room, tend to crowd them out of his never very accommodating public image. He finds many people banal, often unbearably so. He has, in abundance, the sheer mercilessness that Baudelaire attributed to the dandy as a type. People looking for art that will appease their expectations of warmth and unearned self-esteem do well to steer clear of him. Pericolo vipere, as the pathside signs in Italy used to say: danger, vipers.

And then there is the Horse’s Backside. Freud, as is well known, has always been a connoisseur of the gee-gees, a deep plunger at the track, an obsessed student of their form. Not far from where he lives in Holland Park is a riding school, one of whose star horses is a skewbald mare, admired by Freud for her evident self-love: the head wasn’t much, but her backside was magnificent and she revelled in having it patted and stroked. (Any analogy with Freud’s human models may be left on one side.) Freud’s Skewbald Mare, 2004, is an enthusiastic homage to it, and to her. The scheme of colours is very reduced – rich browns, dirty whites. But the brushmarks convey, with marvellous plasticity, the shagginess and density of the animal’s coat, and the muscular strength that underlies it. Headless, it is none the less full of character: it does not read as a fragment or as an incomplete form. Its cropping seems different to photographic cropping.

But it is a striking example of how Freud’s concentration on a motif will conclude it, round its meaning off, even when in another artist’s hands it would be inconclusive. Other depictive artists should look at Freud and either despair or get inspired.