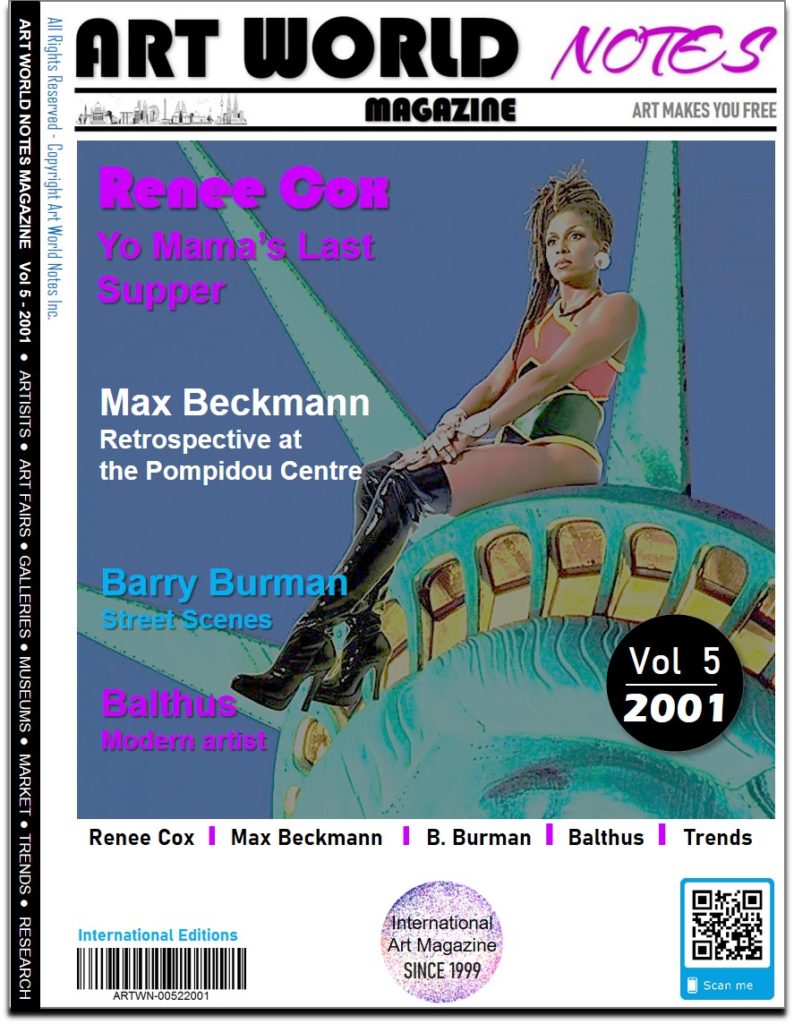

ART WORLD NOTES

MAGAZINE Vol 5

2001 – Semester 01

Renee Cox

Yo Mama´s Last Supper

During communication with poet and journalist Andre Bagoo, he suggested that we look for ways to engage with multiple and disparate voices in our community. By inviting scholars, artists, curators, writers and those connected to the cultural industries in the Caribbean region and its diasporas, to comment one their favorite works of art, we hope that this serves as a platform of education, inquiry and conversation.

Shantrelle P. Lewis, a native of New Orleans, is currently the Director of Public Programming and Exhibitions at the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute (CCCADI) and relocated to Brooklyn in October 2009. For two years, she worked in the capacity of Executive Director and Curator of the McKenna Museum of African American Art. Having received her undergraduate degree from Howard University and master’s degree from Temple University’s Department of African American Studies, Ms. Lewis has demonstrated a commitment to researching, documenting and preserving African Diasporan culture. Additionally, she works with young artists and independently curates exhibits and initiates projects in various cities that are meant to incite, inspire, and shift the paradigms of their audiences.

The racialized, Eurocentric homo-gendered iconography of Catholicism automatically coerces someone existing outside of that spectrum to naturally experience isolation and distancing. This is especially probable for a Black girl child who wondered why nowhere in the Catholic Cathedrals where she genuflected, did she see an image of God in the form of sculpture, oil painting, or stain glass window that looked anything remotely like herself.

What happens then, when that same little Black girl, with Jamaican roots and upper-middle class upbringing, interacts with those negating images? She grows up into a Black woman, or most notably, a “rude gyal” with an attitude, who would thirty-something years later unabashedly confront that iconography, in the form of a series entitled Yo Mama. Although according to Genesis 1:26, God created (wo)man in the image of Him(her)self, nowhere in Christian texts could be found a brown skin God with the face of a girl child from the Diaspora. That is not until Renee Cox decided to photograph herself nude as Jesus surrounded by 12 fully-clothed male disciples, all of them Black with the exception of Judas, who was white, and titled the 5-paneled piece Yo Mama’s Last Supper.

My first time actually seeing Yo Mama’s Last Supper in person was a week ago during a visit to Renee Cox’s uptown studio in Harlem, New York. Back in 2001 when the piece was stirring up controversy with angry Catholics bearing theoretical pitchforks and torches, I was totally unaware of Ms. Cox’s work. At the time, I too was still a practicing Catholic (thanks to my quintessential New Orleans upbringing), and was in the space of trying to figure out what to do with the rest of my life, after recently graduating from Howard University and foregoing the medical career that I spent my entire existence up into that point, training for. I’m not sure how I would have reacted to the news or the image itself had I had the opportunity to interact with Cox’s controversial piece at that juncture in my maturation into adulthood. However, thankfully it wouldn’t be until several years later, after my conversion to African spirituality and an African-centered graduate training that I would come in contact with this work and read it through a particular lens.

Brooklyn Museum’s 2001 inclusion of Yo Mama’s Last Supper in the exhibition Committed to the Image, curated by Barbara Millstein, created controversy that is still memorable more than a decade later. The initial backlash, initiated by then New York City Mayor Rudolph Guilliani, was congruous with historical revisionist theology ascribed to more ancient cosmological systems, beliefs and practices, particularly as they relate to Black people. Despite the fact that the development of monotheism itself was first actualized during the 18th dynasty of ancient Kemet under the rule of the Pharoah Akhenaten and that Jesus Christ is described as an individual with bronze feet and hair like wool, Cox’s audacious decision to confront both the patriarchy and racism persistent in both the structure of the Catholic Church and its iconography, was met with major dissension.